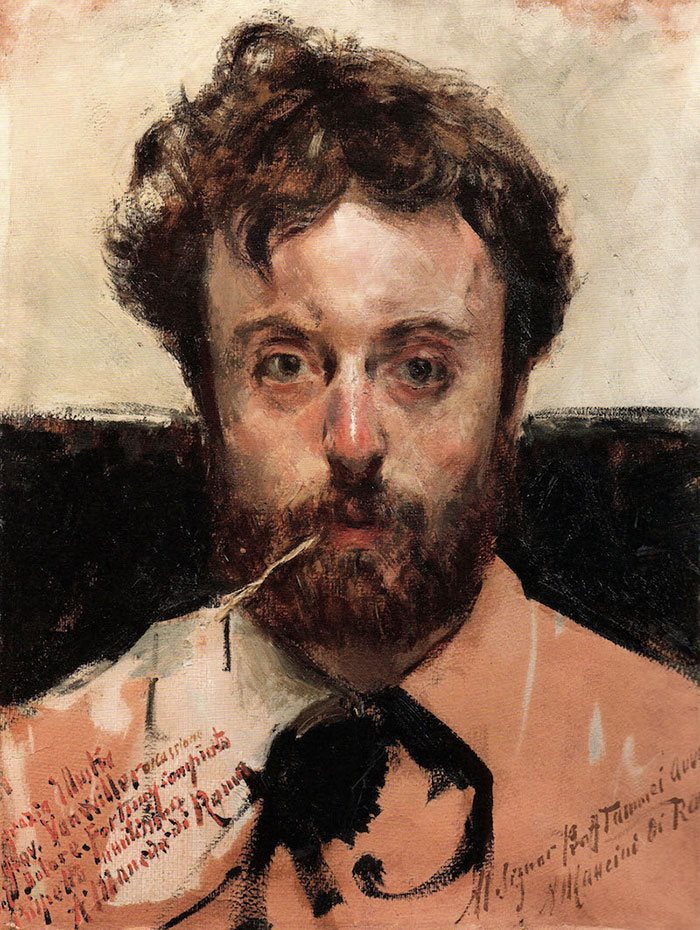

By any standard, the Italian painter Antonio Mancini lived through tumultuous times. He was born in 1852 and died in 1930. In the intervening years Europe experienced the unification of Italy and of Germany, World War I and the rise of communism and fascism.

But mainly Mancini lived through the tumult of being Mancini. This included grinding poverty, mental instability, a personality that swung between extreme timidity and paranoid outrage (vented in long, incoherent letters and stream-of-consciousness journals) and an unusually hectic working method that produced some of the weirdest, most conflicted paintings of the period.

His works tend to be skirmishes of contradictory impulses: academic idealization, gritty realism, bravura society-portrait brushwork and thick, modern-looking impastos slathered and scarred with a palette knife. In some instances it is as if Courbet, Jean-Léon Gérôme and John Singer Sargent — a friend of Mancini’s — have all fallen feverishly to work on the same canvas.